Anthropology home to real life CSI

Bloomsburg

Posted

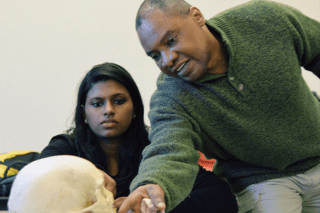

By day Conrad Quintyn, Ph.D. is an anthropology professor at Bloomsburg University. In his spare time, he practices biological anthropology when he willingly wades into crime scenes throughout Pennsylvania. So how does a professor teaching at a public university in rural Pennsylvania become a real-lifecrime scene investigator?

Quintyn served in the U.S. Navy from 1983-1987. Following his military career he continued his education where he found his “passion” for anthropology and crime scene investigation which developed after taking a basic course as an undergrad at Baylor University.

On the walls of Quintyn’s university office hang framed medals, and documents of time spent in the Navy, and working with the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command in Honolulu, a federal government program from 2001-02 which tell the story of his quest to recover the remains of POWs and MIAs.

Braving the dangers of landmines peppered throughout the excavation sites, mainly in Southeast Asia, he and associates exhumed remains of soldiers missing in action hoping to provide answers for families of the soldiers. This cemented hispassion for forensic archaeology and forensic anthropology which led to apursuit of crime scene investigation.

Quintyn’s expertise is sought after regularly by the Pennsylvania State Police for cases both current and cold. He recalls in 2008, his correct identification of tool marks (a saw) on the bones of a dismembered victim of a homicide. “With careful examination of the corpse I assisted police to trace and then arrest the suspect,” says Quintyn. “The investigators found the victims’ hands in the walls of the suspects’ home. The tool marks on the bones of the hands matched those of the mutilated corpse found in trash bags along Route 80 in the Poconos This evidence led to a death sentence for first-degreemurder in 2014.”

Quintyn directed an excavation of a burial in a cemetery in the 2018. A body was exhumed from its resting place to discover if a suspected murderer placed a victim in the open grave of the soon to be buried dead. Carefully guiding the exhumation so as not to disturb surrounding remains, Quintyn discovered only innocentsoil. “No biological, or non-biological material,” he said.

He admits that many of his forays into the forensicworld are fruitless. “Most times, the discovery of remains turn out to be not human,” says Quintyn. But sometimes they do. For instance, Quintyn analyzed human bone fragments recovered from a burn pit on a Weatherly property in 2018. The bone fragments were sent out for DNA analysis by the state police.

Despite this, his commitment to these macabre activities brings closure to the families of the deceased. The stacks of technical reports for the state police are evidence of Quintyn’s labor. Labor for which he accepts no monetary reward. “I do this for the families,” he says quietly. “For closure.”

Quintyn educates his students on the topic of the dead, from human origins, and the evolution of human diseases, to forensic anthropology. After hours, the subject of human remains intertwines with crime scene investigations. If this sounds like a depressing existence, he hasn’t heard the news. As an anthropologist, he is living out one of the American Anthropological Associations’ tag lines … “Advancing knowledge. Solving human problems.”